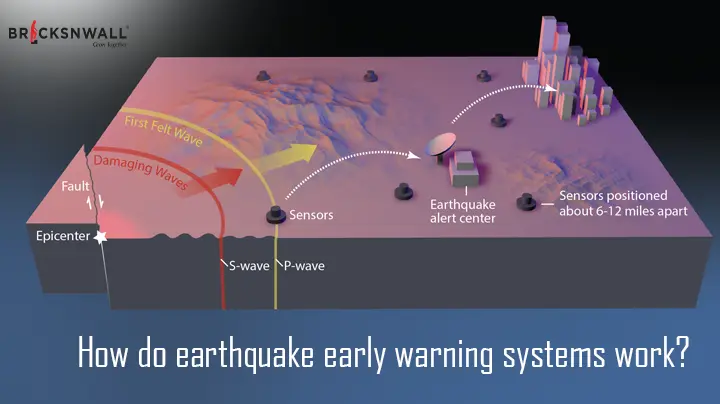

How do earthquake early warning systems work?

Bricksnwall Trusted Experts

Would you

know what to do if an earthquake struck while you were at work? at home?

at gym?

Earthquake

safety researchers want the answer to these questions to be "yes."

Over the

last few years, the United States has implemented ShakeAlert, an earthquake

early warning system for the West Coast. When an earthquake happens, real-time

data from seismometers is used to assess the magnitude of the earthquake and

the locations that will be affected. Individuals and facilities that are likely

to experience strong shaking are then automatically notified. The system is

intended to provide individuals with just a few seconds to defend themselves

before seismic waves arrive; thus everything must happen rapidly for an alarm

to be meaningful.

But

what should people do once they've received the warning?

Creating a

rapid-fire warning system was a technological marvel, but understanding how

people react during an earthquake and what behaviors reduce their chance of

damage presents a whole other set of issues, as researchers detailed in a

recent study regarding the best recommendations to pair with ShakeAlert.

A concise

message

According to

several research, people who have never experienced an earthquake are more

inclined to freeze or run. They may take a break to observe what others are

doing. However, in the event of a big earthquake, a few seconds of uncertainty

could be costly. To be most effective, an alert must be followed with guidance.

"We

know that if a warning is issued without providing people with actionable

information about what to do, the alert will be less effective," says Sara

McBride, the main author of the study and a social scientist at the US

Geological Survey. "Providing an alert with no advice is not really an

option."

The problem

is determining how to provide clear direction to 50 million individuals on the

West Coast who are in different places, doing different things, and have varied

talents.

McBride and

colleagues gathered injury data from a variety of research and locales. The

dangers of earthquakes vary based on building construction, earthquake type,

and even the time of day or season when the earthquake occurs. Previous

research has found that women are more likely to be hurt than men, probably

because they are more likely to be carers and may move around to help children

during shaking.

Inconsistent

data collecting is one difficulty to determining what causes injuries during an

earthquake; after an earthquake, figuring out what an injured person was doing

isn't as vital as providing them treatment. Scientists must also adhere to

ethical data-gathering norms and take trauma into account.

As a result,

this data can be unavailable and acquired over a wide range of time periods,

complicating easy conclusions.

Tripping and

falling while moving, things falling and flying, and the collapse of building

exteriors such as windows and facades have been among the most prevalent causes

of injury during earthquakes in the United States. A widespread misperception

is that a doorway is a good location to go; however, entrances are not a

stronger section of the building and do not shield you from flying debris.

According to

McBride and colleagues' research, the best phrase to accompany an alarm is

"Drop, Cover, Hold On." Getting low to the ground and under a strong

table or desk can shield people from falling objects.

This message

is repeated every year during the Great ShakeOut, the world's largest

earthquake drill, conducted every October. It has also been modified to account

for different skill levels; for example, a wheelchair user should presumably

not drop, but rather lock their wheels, cover their head, and hold on.

Although

there is no one perfect solution for every event, planning and practicing your

actions ahead of time gives you the best chance of surviving.

It is not a

universal message.

The

"Drop, Cover, Hold On" warning has also been adopted by Japan and New

Zealand. In countries with more susceptible buildings, such as Haiti, officials

have decided that evacuation is a better bet. The guidance in Mexico City,

which developed the first earthquake early warning system in 1991, is

location-based. Is living on the first or second floor preferable? Evacuate.

Greater levels? Drop, cover, and hang on.

A geologist at Oregon State University who was not involved in the study emphasizes the importance of individuals knowing the buildings in which they live. Many buildings in Oregon and Washington were constructed before strict earthquake rules were implemented, or perhaps before the Pacific Northwest was recognized as being at risk of a big earthquake. If someone is in a building that is about to collapse and is close to a doorway, Goldfinger believes that getting out is a better option than 'Drop, Cover, Hold On'.